Since its inception three decades ago, the National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture (NAMAC) serves as a facilitator of, and supporting mechanism for the work of the independent media arts. Through collaboration and dialogue with our national community of members, we design programming that fosters and fortifies the field and provides space for independent voices and diverse perspectives to flourish.

We serve our members and the media arts field through: a) conducting and disseminating field-specific research and analysis; b) convening the field in-person and online; c) offering leadership development and other opportunities for professional growth; d) advocating on behalf of the field in Congress and in partnership with leading advocacy organizations.

NAMAC’s Strategic Plan for the next three years calls for increased attention to supporting our youth media members. Over the past year, we have had the great pleasure and privilege of working with a committed – and growing! – group of youth media leaders around the country. We’ve been actively supporting this group’s efforts to lay the foundation for a strong national network that is designed by, and responsive to, youth media’s needs and principles.

Our collaboration with this emerging network builds on NAMAC’s history of involvement with youth media organizations, from the early days of publishing the Youth Media Directory in the 1990s, to the Youth Media Initiative we spearheaded that provided professional development and capacity support to leaders and organizations in the sector. This Initiative helped spur a survey of youth media organizations nationwide, for which we continue to gather data in an effort to draw longitudinal conclusions. The last iteration of this Mapping the Youth Media Field survey was administered in June 2013 by Kathleen Tyner, Associate Professor in the Department of Radio-Television-Film at the University of Texas at Austin. A preliminary overview of the results from this data can be found on the NAMAC website. and Professor Tyner will release a more detailed analysis over the coming months.

Why A National Network?

When NAMAC, as a field-service organization, scans and surveys the youth media sector, in many ways the field looks as it did in 2009 when representatives from youth media organizations gathered at the National Youth Media Summit, a dynamic conversation that led to the influential report, State of the Youth Media Field.

As both the 2009 report and the 2013 Mapping the Youth Media Field survey demonstrate, youth media organizations around the country teach an impressive array of media production skills – video, mobile apps, graphic design, audio / music, social media, games, and more – and as in 2009, youth media organizations continue to provide unique services and learning that students may not otherwise have access to in formal school settings.

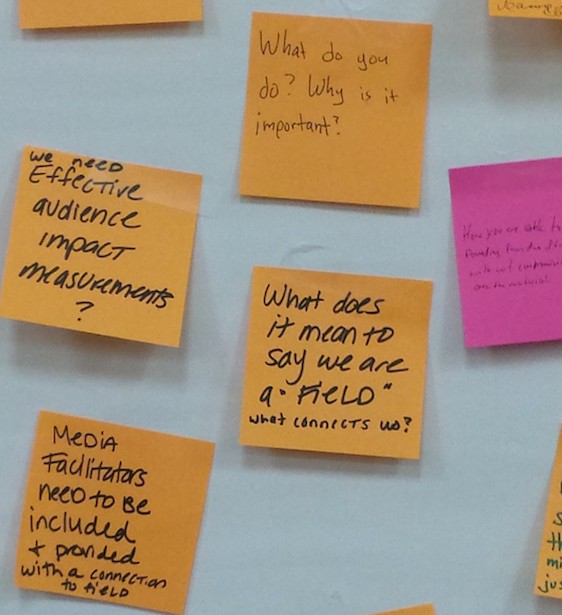

While the youth media community and its supporters clearly appreciate the indispensable work happening in the sector, the question yet remains as to how youth media can make more visible – to parents, funders, and stakeholders– its educational, social, and professional impact on young people’s lives, and by extension, on a participatory, democratic society.

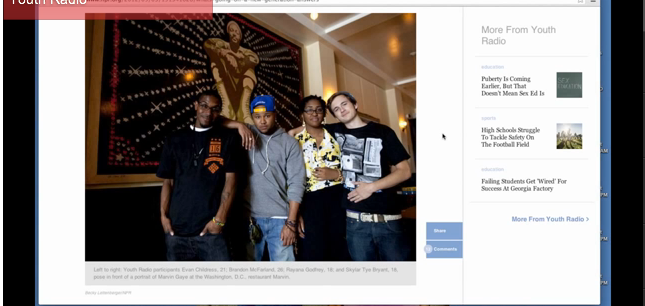

This is not, of course, to say that youth media is invisible. In fact, the 2009 Summit and State of the Field report, as well as more recent developments, demonstrate that the field is a waking giant. In 2012, The Chicago Youth Voices Network, a collaborative of youth media professionals embarked on an evaluation process funded by The Robert R. McCormick Foundation, and supported by the Social IMPACT Research Center. Their study will assess the degree to which hands-on education in media production and distribution contributes to developing productive, independent, and engaged citizens. Then, in 2013, The Wallace Foundation released two extensive publications that lauded the educational gains made in interest-driven and effective after school programs. Featured in these reports were youth media groups such as Spy Hop Productions (Salt Lake City, Utah), Educational Video Center (New York City), the Bay Area Video Coalition (San Francisco, CA), Youth Radio (Oakland, CA), and the Intel Computer Clubhouse Network (National and International).

We can and should also look to the fact that this brief article will be among the body of work that will re-launch Youth Media Reporter as a catalytic voice for the field. As such, Youth Media Reporter will be primed to both discover and share innovative and important developments gleaned from an ever-expanding community of youth media practitioners, educators, researchers, administrators and youth. At the same time, Youth Media Reporter can be a space for thinking through how to share the field’s essential work with new audiences and potential allies across a variety of disciplines.

Unfortunately, while these great steps are being taken, the role of the educator / teaching artist as vehicle for the transmission of media education is increasingly under fire. In an October 2013 Slate article, Lisa Guernsey, the director of the Early Education Initiative at the New America Foundation, describes Hear Me, a Pittsburg-based digital media project that places storytelling kiosks throughout the city so that young people can share their voices and stories. Hear Me, Guenrsey says, “has all the ingredients of a feel-good activity for our time: using digital recorders to capture moments and rebroadcast them; linking technology to physical, face-to-face spaces; and giving students a chance to use new tools for self-expression.”

The project organizers had imagined that they would simply set up a website to collect stories for the storybooths, and because the online platform existed, they would see “kids jumping online and creating audio and video stories about issues in their lives.” It soon became clear that this vision would not come to pass. Young people were not eagerly signing up to contribute content on their own. In regrouping and trying new approaches to generate stories, the researchers learned that “people and kids valued having us, or a third party who has legitimacy and skills to work with kids in the way that we do, visit and bring technology, programming, and ideas to them.” The researchers began partnering with nonprofits, schools, and interviewers to build relationships with young people and gradually acclimate them to the storytelling process. “Under this strategy,” Guernsey writes, “the project has recorded more than 3,700 stories.”

In some corners of the funding world, among portions of the general public, even among some researchers and educators, there is an underlying and insidious assumption that just because (some) young people have access to media technologies by way of cell phones and video games, that this access somehow nullifies the need for a trained educator to guide critical, socially conscious, and transformative use of these technologies. In youth media organizations across the country, we see over and over that not only does an educator serve as a gateway into a rich understanding of the scope, impact, and implications of media technologies, but that a youth media educator is also a professional mentor, a friend, a counselor, and a youth media center itself is a space for community to be built and nurtured. In short, the youth media center and the supportive mechanisms it provides are instrumental to personal, as well as professional, development.

Because unfounded assumptions do exist that equate media access with media literacy, it’s imperative that youth media – and the independent media sector at large – work hard at demonstrating the value of the work we do. While each youth media organization is responsible for sharing their work with their communities, we argue that there is also strength in numbers. In 2009, the field established that the work of youth media can best be strengthened via collaboration, the establishment of federations and/or collectives that provide space for resource sharing, information exchange, and for making visible the work of the sector. In short, youth media’s impact is amplified when organizations across the country connect and fortify a sustainable national network.

For the last decade, youth media has sensed the need for active community building among the manifold organizations that comprise the field. Regional youth media networks have been thriving in various parts of the country: Philadelphia, Twin Cities, Chicago, and recently, the San Francisco Bay Area. These regional groups are able to provide outstanding and unprecedented services to the young people in their communities because the network enables resource sharing, partnering on programming, knowledge exchange, and other practical services that magnify the capacity, visibility, and impact that any one organization could have alone.

Due to geographic constraints, of course, there are some organizations that cannot be served by these regional networks. This is where a national youth media body – whether that be a loose confederation of independent organizations, or a formal nonprofit intermediary with its own funding supply – comes in. This national body could provide a space for organizations and regional networks around the country to connect and readily access each other’s work, innovations, and concerns. It would be a body with many brilliant heads that can amplify the field’s capacity for sharing its work and demonstrating its value. And in this interconnected community, the learners served by youth media could powerfully experience their creative expressions as part of a broader, country-wide effort to develop youth leadership and bolster civic dialogue.

A National Network Emerges

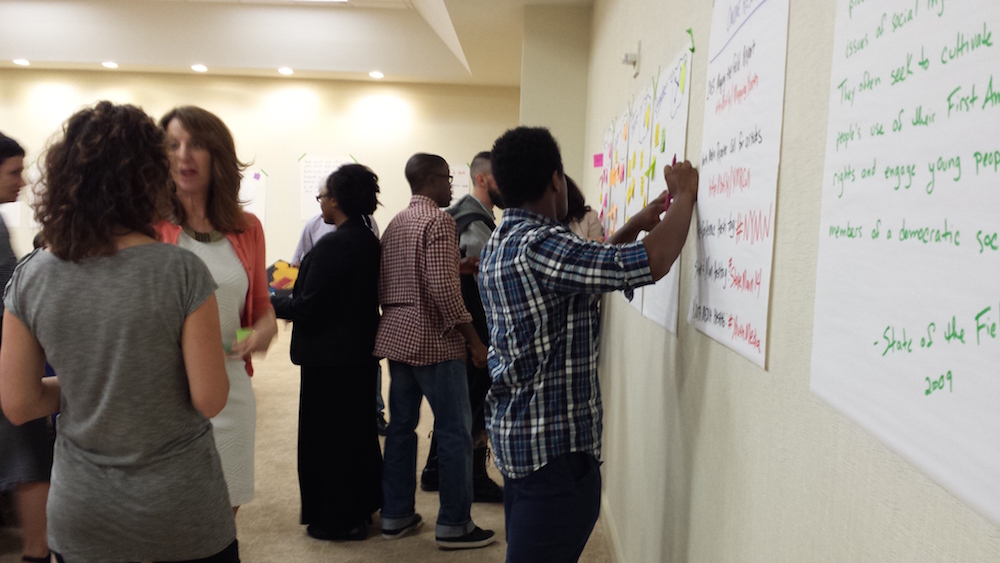

In October 2012, following on the heels of the NAMAC 2012 Leading Creatively conference panel, “Youth Media Networks: How We’re Connected,” a handful of committed youth media leaders, recognizing “the diversity of practices, approaches and experiences of those in [the] field,” started a Google Group email listserv to build upon the conversations they started at the Conference. “We see the opportunity to strengthen our work by creating stronger connections among us,” they wrote in their first public announcement on the listserv.

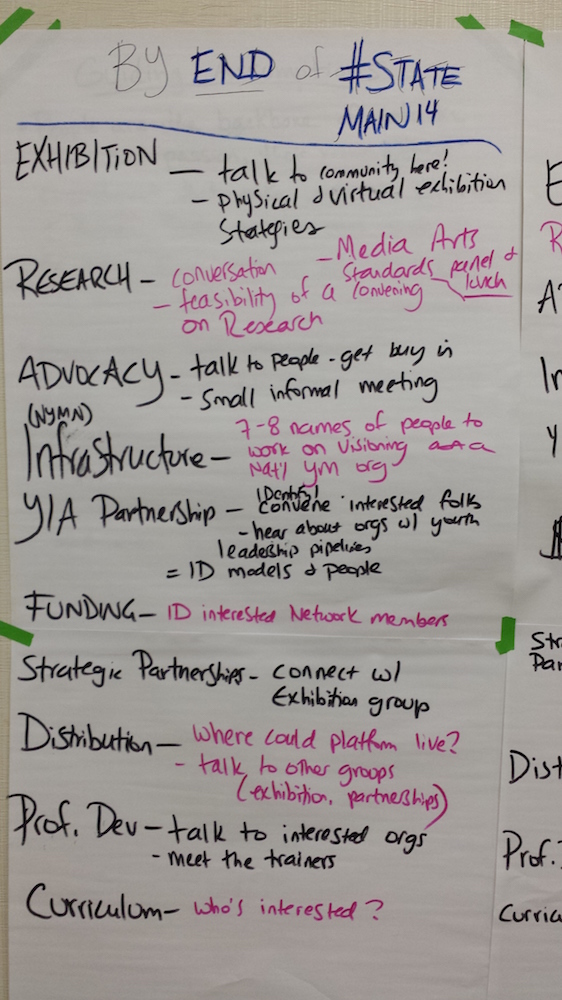

NAMAC offered to help promote the efforts of this emerging National Youth Media Network by providing field building, coordination, and administrative support where needed. After some initial surveying of the field, the organizers decided to launch a series of bi-monthly Connector Sessions: online conversations intended to a) explore topics of relevance to youth media practice, such as assessment, curriculum development, STEM funding, etc.; and to b) initiate an incremental community building and brainstorming process to help elucidate what a national network might look like and in what ways it could serve the field.

As a testament to how the pragmatic conversations in the Connector Sessions can lend field-building insight, consider this sampling of questions raised in the first Connector Session on “Emerging Media Arts Standards,” hosted in March 2013. In this Connector, the Chair of the Media Arts Standards Writing Committee of the National Coalition of Core Arts Standards, Dain Olsen, explained the significance of developing educational standards written specifically to meet “learners’ growing needs in the emerging digital media context.” Questions raised by participants included:

- What do you think the development of assessment tools, will look like [under the Media Arts Standards]? And how can those assessment tools be used with lesson plans and curriculum?

- Could you talk briefly about how you see the standards and framework that you’re evolving, make space for or articulate or sustain the enduring commitment within youth media to its abiding youth-drivenness?

- To what extent are media literacy and media analysis a part of the standards here, from an analytical perspective?

In these questions alone, we catch a glimpse of the diversity of perspectives, modalities, and needs in youth media practices across the country. By bringing diverse voices into regular conversation, we can collectively and specifically imagine a national network that is responsive to many, if not all, of these multi-faceted needs.

As the Connector Sessions continue to serve as an interesting and sustainable model for convening the field, the Google Group email listserv has grown incrementally, as has the core group of National Youth Media Network organizers. Currently, we number twelve organizers and over one hundred Google Group members. We have proposed and presented at two conferences: the Alliance for Community Media Conference (ACM) conference and the National Association for Media Literacy Education Conference (NAMLE). Representatives from ACM and NAMLE, involved as they are in supporting youth media and media education, have in fact joined the organizing committee.

From the great strides taken by the committed group behind the National Youth Media Network, we’ve seen that the question before the field is not whether there will be a national networking body, but when and how. What will that national network look like? Who will lead it? What services would this national network provide? Will it need funding? If so, what sources would honor “youth media’s youth-drivenness” as well as its commitment to critical pedagogy? What cross-sector alliances could it forge to benefit the field? And what will be the role of the national intermediaries, NAMAC, NAMLE, ACM, and of Youth Media Reporter in this ongoing field-building work?

While organizations like NAMAC exist to create spaces in which such questions can be raised, ultimately only youth media organizations, students, and educators themselves will be able to provide the answers. We look forward to witnessing – and supporting – the field’s continued evolution.

Bibliography

Ingrid Dahl, “State of the Youth Media Field Report,” Youth Media Reporter, November 2009, http://www.youthmediareporter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/SOF-FINAL-Nov24.pdf.

Lisa Guernsey, “Voices Carry: A Kids’ Tech Project Gets Real,” Slate, October 2013, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2013/10/hear_me_pittsburgh_project_how_to_use_technology_to_help_kids.html.

Notes

Regardless of who or how this work is going to get done, the CYD movement is a growing national effort to elevate very similar work that so many of us in youth media have been doing for years; yet, our two groups are largely disconnected. The CYD policy agenda is rooted in strategies around youth leadership, cross-sector collaboration, sustainable funding models, and communicating impact on a broad scale – much of the same strategies that youth media organizations have been employing for years. While there is no doubt overlap in the numbers, if you combine 200 organizations with the nearly 100 within youth media, we are significantly impacting the lives of hundreds of thousands of young people across the country!

Regardless of who or how this work is going to get done, the CYD movement is a growing national effort to elevate very similar work that so many of us in youth media have been doing for years; yet, our two groups are largely disconnected. The CYD policy agenda is rooted in strategies around youth leadership, cross-sector collaboration, sustainable funding models, and communicating impact on a broad scale – much of the same strategies that youth media organizations have been employing for years. While there is no doubt overlap in the numbers, if you combine 200 organizations with the nearly 100 within youth media, we are significantly impacting the lives of hundreds of thousands of young people across the country!