Author’s Note:

A few years ago, after reading Peter Gray’s 2013 essay, The Play Deficit (cited below), I was so reminded of my own childhood learning through play that I felt obligated to discuss the article with my closest childhood friends, with whom I’m privileged to still have as integral part of my social circle. At the time I didn’t know if I would continue working in youth development, but now, as I coordinate the Youth Media Department at a community media center, I keep coming back to this conversation; my thoughts in that conversation, updated with further research and experience, formed the foundation for this essay.

“The imagination is essential for moral action. Because unless one can imagine predicaments other than one’s own, one would never act to alleviate or to remediate those predicaments. We would all be narcissists. And the only cure for the narcissism that comes of the natural parochialism of inherited circumstances…the only thing that corrects for that is empathy, the only thing that creates empathy is imagination, and the only thing that schools and trains the imagination are the arts and the humanities. So in a sense, art is a foundation of empathetic, ethical action—the very foundation for it…. It is that fundamental.”

-Drew Gilpin Faust

Where I live, the Twin Cities of Minneapolis-St. Paul, we have one of the largest achievement gaps in the country—a divide between those students who are afforded the conditions to succeed, and those who are not. And although our conventional definitions of and requirements for “success” are certainly part of the problem, it’s no doubt that there’s a lot of work cut out for those of us involved in the education and support of Minnesota youth. Resonant, engaging storytelling will be an understated but vital part of our local and national healing, more important now than ever before. In an era of media quickly becoming defined by fake news, a denial of bias and the miscalculation of media literacy training, how do we identify and relate stories that can bridge the gap of understanding, let alone of academic and professional achievement? When the stories of our collective futures are still so hard to see, we need to invest in play to help us imagine them. Because play is necessary to investigate the imagination, and imagination is necessary to envision new ways to understand our past, our current standing in the world, and our potential futures. And we can go even further with play that is collaborative, to network our imaginations into wholly new visions altogether.

As media makers and educators, there should be play in everything we do. Without it we lose our ability to create new ideas, to inspire ourselves and others, and to rejuvenate our minds. That may sound bold, depending on your definition of “play”; it is a word that means a great many things, depending on who you’re talking to. For us, let’s define “play” as the practice of taking risks on matters of the imagination. When we play, broadly speaking, we engage in imagining a potential (even if only a fantastically potential) event or sequence of events. And within that realm of the imagination, we make educated presumptions and actions based on these presumptions. This doesn’t just apply to well-defined games and young children playing pretend. Play is trial and error, helping us find what works and what doesn’t. Play is internal, private, and play is social and collaborative. Play is the basis for all creative experimentation. And this of course is a necessary aspect of creative problem solving and overall youth (human) development. People who frequently engage in play can learn more from their mistakes because they’re doing it all the time. And it’s only through taking risks, often failing more than not, that we can learn new ways to succeed.

There’s much more to play than having fun. It helps us develop strategies and understand experiences that occur in the rest of our lives. It’s an integral part of our lives, and we’ve been doing it for as long as we’ve been a species. As play-theorist Bernard de Koven recollected last year:

“The excitement that kept me writing came from the discovery that I wasn’t really writing just about games and play. Every time I put the practices of play into words I experienced a kind of resonance with something that penetrated much deeper: into society and morality, community and culture, art and religion, politics and human nature. I’d write about strategies for a game kids play in kindergarten and learn, some thirty years later that I was also revealing strategies for surviving in the Death Camps. I’d describe an experience I had playing ping pong with a friend and find that I was writing about an experience of communion with the divine.”

But keeping play at the heart of our work can be difficult in the context of curricula standards, grant reporting requirements, and the ever-growing need to find measurable data to keep the lights on and the cameras running. Play, and its role in imagination and creativity is not always able to provide us with the tangible data funders of youth development or the arts like to see. Likewise, media literacy is inherently harder to measure than, say, English literacy, and one student’s new ability to share her truth is harder to prove than how many students passed a test on using this or that kind of software. Both are important, sure, but our priorities often slide into numbers and graphs—things that can be represented in a PDF for easily consumable grant reporting. As much as out-of-school-time youth workers may try, we end up falling into traps of borrowing from rigid standards, to fit into often too-narrow funding restrictions.

I would never claim that English literacy isn’t an important skill in the 21st century United States. But when you think back to the learning that defined your childhood—the things that really made you “grow up”—were they reading tests? I doubt it. Standardized tests, as are so often derided by us education professionals, are anathema to learning. Instead of diagnostic, they have become prescriptive. Teachers spend precious time and resources ensuring that their students will be able to pass tests, and are left without enough time to invest in the kind of learning our students will really need for a rapidly changing future. The kind of learning that expands divergent thinking. We all have the capacity for divergent thinking as children—the ability to see many possible ways to interpret a question, and many answers—but it generally deteriorates as we go through the education system, rather than develops; as a society, we’re having our creativity educated out of us. And as educationalist Ken Robinson has said, “in place of curiosity, what we have is a culture of compliance. Our children and teachers are encouraged to follow routine algorithms rather than to excite that power of imagination and curiosity…. We all create our own lives through [the] process of imagining alternatives and possibilities, and one of the roles of education is to awaken and develop these powers of creativity. Instead, what we have is a culture of standardization.”

That leaves a lot of this work to out-of-school-time learning. As a child, I was always encouraged to join more extracurriculars. “Colleges like to see that,” I was told. This may be true, and I did join a few structured activities, between Cub Scouts, summer camps and organized sports. But looking back, what had the greatest effects on me—the activities that taught me how to think about things differently and adapt to new problems— weren’t these structured, organized activities where I was told what to do and how to do it. What outlined the greatest learning in my childhood were the moments of unstructured, creative play—independent and collaborative—that I engaged in.

The play I engaged in as a kid revolved around media—writing stories about my favorite cartoon characters, making stop motion Lego animations, recording angsty songs. Looking back, I can’t help but cringe. But I also can’t deny what that play has done for me. Writing stories about fictional characters helped me see my own actions and the actions of my friends from an outsider’s perspective. Using Legos to create science-fiction animation made me think about the technical process of animation, but more importantly, made me consider what a future world might look like, visually, culturally and ethically; it made me consider why the “bad guys” did what they did, and wonder if the “good guys” could ever be misguided. Role playing on the playground during recess helped me define my values; who I wanted to be and who I didn’t want to be. And more than anything else, these things helped me find voice. My friends and I learned systems of play together—N64 and Xbox, the board games we made, the music we produced together—and once we taught each other how to be proficient in those systems, we continued to negotiate, react to and create narratives around them. We used them to analyze our own lives and desires for our futures, and we learned to point to and create analogies between fictions and realities.

Between pulling each other on skateboards with bungie cords connected to the backs of our bikes, or putting our most vulnerable selves on stage for all our friends to judge, we learned through these risks—playful experiments—with stakes that we set for ourselves. This sort of unstructured play, and the community we built together, was so vital to our development as people—but what if we’d had access to greater resources and mentorship? My grandfather, for example, instilled in me a love for craft, by teaching me how to make model cars and airplanes. This fueled my imagination for career, for working with my hands, and for an eye for detail. Now imagine if the games that my friends and I had created had been backed by mentoring relationships with older peers who could’ve helped us learn and inspired us to continue learning? Or the music, or the animations? What could we have done under conditions where we had better mentorship, resources, and community? Where those mentoring relationships would have been able to teach us not just the skills of our interests, but been a one-stop resource for all our questions, be them social, professional, or whatever.

Hopefully many reading this have experienced those conditions for themselves. As an educator in the media arts, I see my students and teen interns engaging in the same kind of play. And I am privileged to serve as that mentor. Working with youth to guide their passions (or sometimes just their curiosity) for media production through an in-depth process of creation proved to me that when teens craft media that speaks to their lives and concerns, they develop new ways of seeing the issues they’re approaching. It’s often the kind of collaborative play that Henry Jenkins talks about in regards to participatory culture—online and other communities that embrace multi-level learning to teach and produce social narrative-creation, and then using the skills they develop to, in his words, “find a vehicle to think politically through these kinds of interest-driven networks,” whether that be through political advocacy for domestic labor rights, or fighting human rights abuses abroad. The ability to define and craft narratives about our lives and socio-political contexts takes us to the next step of redefining how we understand our lives and contexts—in past and present—and of devising steps to understand and make happen our desired futures.

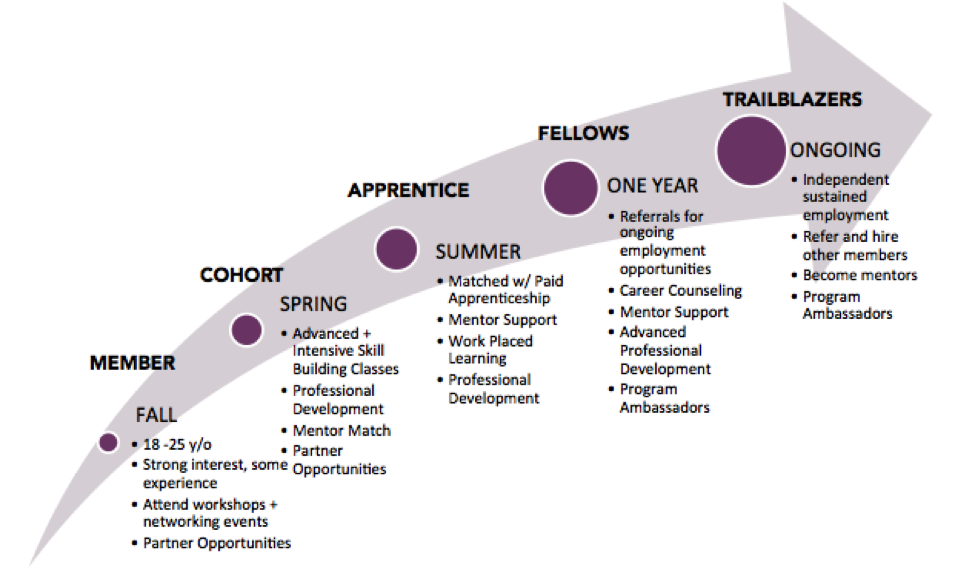

By providing teens with a place and space to engage with narrative creation, to dissect the stories they watch and to gradually—and often chaotically—piece together new stories through negotiating with each other, we’ve formed a community that continues to grow and develop, based around our mentorship. We empower them to investigate their passions and create the narratives they want to tell. And on top of that, they learn technical skills, job preparation, and are guided in social-emotional development like collaboration and self-reflection. After all, we’re not just preparing them as media-creators and fellow people; we have a duty to help prepare them for a future that we can’t yet imagine, where work may appear wholly different than it does today.

Lately I’ve noticed some of our students are moving away from interests in documentary media. They say “I just want to help people laugh. To help people de-stress.” There’s a need for escapism there, but there’s also a vision for a reality that’s more lighthearted than our everyday experiences. A vision of optimism. For a couple years now, I’ve assigned a day for students to compete in our own Worst Short Film Ever competition. This is one of the most playful days of the year, and helps teach our teens what not to do the rest of the time we meet. Students have an hour to write, film and edit the “worst short film ever”; the results can be hilarious or excruciating—and sometimes both—but they are always great stretches for teens to think about what they could possibly do to produce something worse than their peers. And in being asked to imagine a pinnacle, they take step one to make it happen.

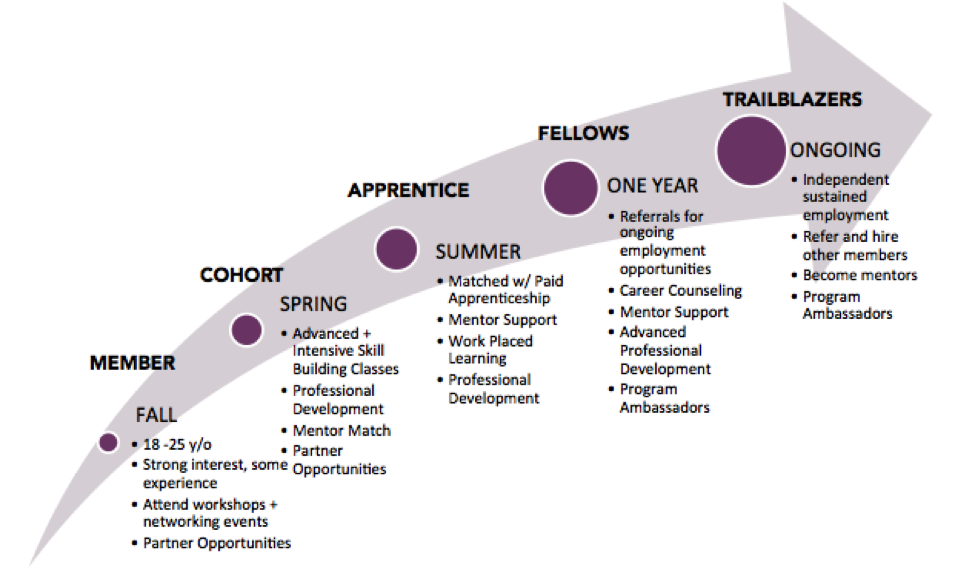

For me, that’s the true power of youth media programming. Some of our teens are already making innovative, creative, sometimes weird and sometimes civically-engaged work before they walk in our doors. Some of them don’t have the resources until they get here. But our programs and mentorship serve as a one-stop resource for their systems of play; play that results in professional development, new visions for their futures, new skills and new friendships. As psychologist Peter Gray wrote, “children are biologically designed to educate themselves, through play and exploration; we don’t need to educate them, we need to provide the conditions to allow them to educate themselves.” What are these conditions? In our field, they include access to equipment and a safe space—a place and space to hang out, mess around, geek out. As media makers, both youth media educators and learners, we have many unique responsibilities. The most important of those might be to be able to create new narratives with which we can understand our lives and our possible futures. Without being able to speculate our future narratives, we have no way to imagine new ways to guide our futures for the better.

This isn’t the final solution to closing the achievement gap of course, locally or nationally. This isn’t going to make our students’ or our own hardships go away, or change every policy creator’s mind about serving the needs of those students who continue to be disserved. But it can be a beginning. And it can provide hope where seemingly none may have existed before. Play is, above all, about taking risks, failing, and learning. There’s a lot of talk about taking risks, but it’s about time we normalize the latter two as well. Because the most impactful lessons start with making mistakes together, and end with making change together.

About the Author

Jordan Lee Thompson is an art worker and educator who has been working with digital media production since he was 12 years old—starting with stop-motion Lego animations, through a period of recording angsty folk-rock in high school, to creating obscure projection-performance art in college. Jordan now works in a variety of mediums including performance, installation, video production, projection, drawing, animation and other new media to combine his passions of participatory art, critical theory, sociology and storytelling. Jordan spends his days at CTV North Suburbs where he directs the Youth Media Department, helping teens write, produce and distribute their own short films, and serves as the Film Festival Coordinator for Mizna’s Twin Cities Arab Film Festival. Most recently, Jordan co-produced The Beginning of Things + Fictions in a guest residency at the Southern Theater’s ARTshare program as Creative Director of Dance & Other Behaviors. Jordan has also worked with organizations including James Sewell Ballet, the Minneapolis Television Network, and the Twin Cities Media Alliance. Jordan holds a BFA in Painting, a BA in Art History and Arts Management, and a certificate in Museum Studies from the University of Iowa.

Stacey Daraio brings 30 years of experience working in the field of youth development as a designer, facilitator, trainer, evaluator, and coach. She has experience training and coaching diverse audience groups, from afterschool practitioners to funders and technical assistance providers. In her prior life she did professional theater, both acting and directing and was a drama therapist. She lives in San Francisco with her partner Kari, two children—Keana and Kai, and two creatures—a husky, Coda and a cat, Simon. Left to her own devices, she would be either sitting in the sun with a book and cup of coffee, or curled up on the couch with the creatures (all of them!), a book and cup of coffee.

Stacey Daraio brings 30 years of experience working in the field of youth development as a designer, facilitator, trainer, evaluator, and coach. She has experience training and coaching diverse audience groups, from afterschool practitioners to funders and technical assistance providers. In her prior life she did professional theater, both acting and directing and was a drama therapist. She lives in San Francisco with her partner Kari, two children—Keana and Kai, and two creatures—a husky, Coda and a cat, Simon. Left to her own devices, she would be either sitting in the sun with a book and cup of coffee, or curled up on the couch with the creatures (all of them!), a book and cup of coffee.

treet was born and raised in Oakland, California, and studies Journalism and English Literature at San Francisco State Univ

treet was born and raised in Oakland, California, and studies Journalism and English Literature at San Francisco State Univ